With Doug Aamoth and Paul Ducklin.

DOUG. More extortion scams, more crypto theft, and a bugfix for a bugfix.

All that more on the Naked Security podcast.

[MUSICAL MODEM]

Welcome to the podcast, everybody.

I am Doug Aamoth, and he is Paul Ducklin.

Paul, how do you do?

DUCK. I am super-duper, thank you, Douglas.

DOUG. We like to start the show with a little bit of tech history, and I’d like to remind you that this week, in 2007, the first generation iPhone was released in the United States.

At a time when most high-end phones were selling for $200 with a two-year wireless service contract, the iPhone started at $500 with a two-year contract.

It also sported a slower connection speed than many phones at the time, with 2.5G, or EDGE, versus 3G.

Still, two-and-a-half months after its release, Apple had sold a million iPhones.

In the US alone.

DUCK. Yes, I’d forgotten that thorny detail of the of the 2-dot-5 EDGE!

I just remember thinking, “You cannot be serious?”

I was in Australia at the time, and they were *expensive*.

I think that was still the era when I was just hanging onto my EDGE device… I keep calling it a JAM JAR, but it was actually called a JASJAR or a JASJAM, or something.

One of those sliding-keyboard Windows CE devices.

I was the only person in the world that loved it… I figured, well, someone has to.

You could write your own software for it – you just compiled the code and put it on there – so I remember thinking, this App Store thing, only 2.5GG, super-expensive?

It will never catch on.

Well, the world has never been the same since, that’s for sure!

DOUG. It has not!

All right, speaking of the world not being the same, we’ve got more scams.

This one…why don’t I just read from the FTC about this scam?

The FTC (the Federal Trade Commission in the United States) says the criminals usually work something like this:

“A scammer poses as a potential romantic partner on an LGBTQ+ dating app, chats with you, quickly sends explicit photos, and asks for similar photos in return.

If you send photos, the blackmail begins.

They threaten to share your conversation and photos with your friends, family, or employer unless you pay, usually by gift card.

Other scammers threaten people who are closeted or not yet fully out as LGBTQ+. They may pressure you to pay up or be outed, claiming they’ll ruin your life by exposing explicit photos or conversations.

Whatever their angle, they’re after one thing your money.”

Nice people here, right?

DUCK. Yes,. this is truly awful, isn’t it?

And what particularly caught me about this story is this…

A couple of years ago, the big thing of this sort, as you remember, was what became known as “sextortion” or “porn scamming”, where the crooks would say, “Hey, we’ve got some screenshots of you watching porn, and we turned on your webcam at the same time. we were able to do this because we implanted malware on your computer. Here’s some proof”, and they’ve got your phone number or your password or your home address.

They never show you the video, of course, because they don’t have it.

“Send us the money,” they say.

Exactly the same story, except that in that case we were able to go to people and say, “All a pack of lies, just forget it.”

[embedded content]

Unfortunately, this is exactly the opposite, isn’t it?

They *have* got the photo… unfortunately, you sent it to them, maybe thinking, “Well, I’m sure I can trust this person.”

Or maybe they’ve just got the gift of the gab, and they talk you into it, in the same way as traditional romance scammers… they don’t want explicit photos for blackmail, they want you to fall in love with them for the long term, so they can milk you for money for weeks, months, years even.

[embedded content]

But it is tricky that we have one kind of sexually-related extortion scam where we can tell people, “Don’t panic, they can’t blackmail because they actually don’t have the photo”…

…and another example where, unfortunately, it’s exactly the other way around, because they do have the photo.

But the one thing you should still not do is pay the money, because how do you ever know whether they are going to delete that photo.

Even worse, how do you know, even if they actually are – I can’t believe I’m going to use these words – “trustworthy crooks”?

Even if their intention is to delete the photo, how do you know they haven’t had a data breach?

They could have lost the data already.

Because dishonour among thieves and crooks falling out with one another is common enough.

We saw that with the Conti ransomware gang… affiliates leaking a whole load of stuff because they’d fallen out with the people at the core of the group, apparently.

And lots of cybercrooks have poor operational security themselves.

There’s been any number of cases in the past where crooks either ended up getting bust or ended up giving away the secrets of their malware because their systems, where they were supposedly keeping all the secrets, were wide open anyway.

DOUG. Yes.

At a very personal and uncertain time in people’s lives, of course, when they finally trusted someone they’ve never met… and then this happens.

So that’s one of our tips: Don’t pay the blackmail money.

Another tip: Consider using your favorite search engine for a reverse image search.

DUCK. Yes, lots of people recommend that for all sorts of scams.

It’s very common that the crooks will gain your trust by picking an online dating profile of someone that they’ve pre-judged you’ll probably like.

They go and find someone who actually might be a good match for you, they rip off that person’s profile, and they come steaming in, pretending to be that person.

Which gets them off to a very good start when it comes to romantic machinations, doesn’t it?

And so, if you do a reverse image search and somebody else’s profile comes up: bingo! You’ve busted them!

The bad news is that you can’t use that to prove anything about the people…

…in other words, if you do the reverse search and nothing comes up, it doesn’t mean that the person you’re speaking to really is the original owner of that photograph.

However, we have had people on Naked Security commenting saying, “I got one of these; I did a reverse image search; it instantly came out in the wash. Reverse search worked really well for me.”

You might trip the cook up at the very, very first hurdle.

DOUG. Yes, I think I shared this in one of the first podcast episodes we did…

We were trying to rent a ski-house, and the place we were trying to rent looked a little too good to be true for the price.

And my wife called the person to ask them about it, and clearly woke someone up in the middle of the night on the other side of the world.

As she was doing that, I dropped the image into a reverse image search, and it was a Ritz Carlton Hotel in Denver or something like that.

It was not even close to where we were trying to rent.

So this works beyond just romance scams – it works for anything that just smells kind of fishy, and has images associated with it.

DUCK. Yes.

DOUG. OK. And then we have the tip: Be aware before you share.

DUCK. Yes, that’s one of our little jingles.

It’s easy to remember.

And, in fact, it’s not just true for these sexual extortion scams, although, as you say, it’s especially troubling and evil-sounding in such cases.

It’s absolutely true in all cases where there’s someone that you’re not sure about – don’t give out information, because you can’t get it back later.

Once you’ve handed over the data, then you don’t just have to trust them… you have to trust their computer, their own attitude to cybersecurity and everything.

DOUG. That dovetails nicely with our next tip, which is: If in doubt, don’t give it out.

DUCK. Yes, I know some people say, “Oh, well, that sounds like you’re victim blaming.”

But once you hand out your data, you can *ask* for it back, but you can’t really do much more than that.

It’s trivial to share stuff, but it’s as good as impossible to call it back afterwards.

DOUG. OK, then we’ve got some resources in the article about how to report such scams based on the country that you live in, which is pretty handy.

DUCK. Yes, we put in online fraud reporting URLs for: the USA, the United Kingdom, the European Union, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

The US one is https://reportfraud.ftc.gov.

And the FTC, of course, is essentially the consumer rights body in the United States.

I was very pleasantly surprised with that site – I found it very easy to navigate.

You can put in as much or as little information as you want.

Obviously, if you want to keep up with a case later, then you’re going to have to share information that allows them to contact you back – in other words, it would be difficult to remain completely anonymous.

But if you just want to say, “Look, I’ve got this scam, I must be one of a million people”…

…if nobody says anything, then essentially, statistically, nothing happened.

You can report things and just say, “I got this URL, I got this phone number, I got this information,” whatever it is, and you can provide as much or as little as you want.

And although it sometimes feels like reporting this stuff probably doesn’t make a difference – because obviously if you don’t give your email address and your contact details, you won’t get any reply to say whether it was useful or not – you just have to take it on faith.

And my opinion is: I don’t see how it can possibly do any harm, and it may do a little bit of good.

It may help the authorities to build a case against somebody where, without several corroborating reports, they might have found it very difficult to get to the legal standard they needed to actually do something about what is a particularly nasty crime.

DOUG. OK, that is: FTC warns of LGBTQ+ plus extortion scams: Be aware before you share” on nakedsecurity.sophos.com.

And speaking of being aware, when are we going to have one week where we’re not aware of some sort of crypto theft?

Another $100 million vanished into thin air, Paul!

DUCK. I didn’t realise that was a rhetorical question.

I was about to chime in and say, “Not this week, Doug.”

Actually, when you look at the current exchange rate of US dollar to Ether, I wonder if this one was even worth writing about. Doug?

It was not quite $100 million… It was, “I don’t know, $80 million, $90 million – it’s almost not worth getting out of bed to write about,” he said

very cynically.

Yes, this was yet another decentralised finance, or De-Fi, company disaster.

You wouldn’t know it to go to their website.

The company is called Harmony – they’re essentially a blockchain smart contract company… you go to the website, and it’s still full of how great they are.

If you go to their official blog from their website, there is a story on there which is “Lost Funds Investigation Report”.

But that’s not *these* lost funds; that’s *those* lost funds.

That’s from back in January… I think it was “only” something like a $5 million hack, maybe even less, Doug, that somebody made off with.

And that’s the last story on their blog.

They do have information on Twitter about it, to be fair, and they have published a blog article somewhere on Medium.com which details what little they seem to know.

It sounds like they had a whole lot of funds that were locked up centrally, funds needed to make the wheels work, and to allow those things to be moved in and out, they were using what’s called a “multi-signature” or “multisig” approach.

One private key wouldn’t be enough to authorise transferring out any of these particular funds.

There were five people who were authorised, and two of them had to come in together, and apparently each private key was stored sort-of split in half.

The person had a password to unlock it, and they needed to get some key material from a key server, and apparently each private key was on a different key server.

So, we don’t know how it happend… did somebody collude? Or did somebody just think they’d be really clever and say, “Hey, I’ll share my key with you, and you share your key with me, just in case, as extra backup?”

Anyway, the crooks managed to get two private keys, not one, so they were able to pretend to be more than one person, and they were able to unlock this large amount of funds and transfer it to themselves.

And that added up to some $80 million-plus US dollars worth of Ether.

And then, it seems, that Harmony, like they did back in January when they had the previous rip-off… they did that what everyone’s doing these days.

“Dear Mr. White Hat, dear Lovely Crook, if you send the funds back, we’ll write it up as a bug bounty. We’ll rewrite history, and we’ll try not to let you get prosecuted. And we’ll say it was all in the name of research, but please give us our money back.”

And you think, “Oh, golly, that smacks of desperation,” but I guess that’s all they’ve got to try.

DOUG. And I like that they’re offering 1% of what was stolen.

And then the icing on the cake is they will “advocate for no criminal charges” when funds are returned, which seems hard to guarantee.

DUCK. Yes, I guess that’s all they can say, right?

Well, certainly in England, you can have things called private prosecutions – they don’t have to be brought by the state.

So you could do a criminal prosecution as a private individual. or as a charity, or as a public body, if the state doesn’t want to prosecute.

But you don’t get the opposite, where you’re the victim of a crime and you say, “Oh, I know that guy. He was drunk out of his mind. He crashed into my car, but he repaired it. Don’t prosecute him.”

The state will probably go, “You know what? It’s actually not up to you.”

Anyway, it doesn’t seem to have worked.

Whoever it was has already transferred something like 17,000 Ether (something just shy of $20 million US, I think) out of the account where they’d originally collected the stuff.

So, it’s looking as though this is all going down the gurgler. [LAUGHS]

I don’t know why I’m laughing, Doug.

DOUG. This just keeps happening!

There’s got to be a better way to lock down these accounts.

So, they’ve gone from two parties having to co-sign to four parties.

Now, does that fix this problem, or will this keep happening?

DUCK. “Hey, two wasn’t enough. We’ll go to four.”

Well, I don’t know… does that make it better, or the same, or worse?

The point is, it depends on how the crooks, and why the crooks, were able to get those two keys.

Did they just target the five people and they got lucky with two of them and failed with three, in which case you can argue that making it four-out-of-five instead of two-out-of-five will raise the bar a bit further.

But what if the system itself, the way that they’ve actually orchestrated the keys, was the reason the crooks got two of them… what if there was a single point of failure for any number of keys?

And that’s just what we don’t know, so just go from two to four… It doesn’t necessarily solve the problem.

In exactly the same way that if someone steals your phone and they guess your lock code and you’ve got six digits, you think, “I know, I’m going to go to a ten-digit lock code. That will be much more secure!”

But if the reason the crooks got your lock code is that you have a habit of writing it down on a piece of paper and leaving it in your mailbox just in case you’re locked out of your house… they’ll go back and get the ten-digit, the 20-digit, the 5000-digit lock code.

DOUG. All right, well, we’ll keep an eye on that.

And something tells me this won’t be the last of these stories.

This is called: Harmony Blockchain loses nearly $100 million due to hacked private keys, on nakedsecurity.sophos.com.

And now we’ve got a bug fix for a bug fix in OpenSSL.

DUCK. Yes, we’ve spoken about OpenSSL several times on the podcast, mainly because it’s one of the most popular third party cryptographic libraries out there.

So, lots of software uses it.

And the problem is that when it has a bug, there are loads of operating systems (particularly lots of Linux is shipped with it) that need to update.

And even on platforms that have their own separate cryptographic libraries, like the Windows and the macOS systems of the world, you may have apps that nevertheless bring along their own copy of OpenSSL, either compiled in or brought along into the application folder.

You need to go and update those, too.

Now, fortunately, this is not a super-dangerous bug, but it’s kind of an annoying sort of bug that’s a great reminder to software developers that sometimes the devil’s in the details that surround the trophy code.

This bug is another version of the bug that was fixed in the previous bugfix – it’s actually in a script that ships along with OpenSSL, that some operating systems use, that creates a special searchable hash, an index, of system “certificate authority” certificates.

So it’s a special script you run called c_rehash, short for “certificate rehash”.

And it takes a directory with a list of certificates that have the names of the people who issued them and converts it into a list based on hashes, which is very convenient for searching and indexing.

So, some operating systems run this script regularly as a convenience.

And it turned out that if you could create a certificate with a weird name with magic special characters in it, just like the “dollar-sign round brackets” in Follina or the “dollar-sign squiggly brackets” in Log4Shell… basically they would take the file name off disk, and they would use it blindly as a command shell command line argument.

[embedded content]

Anyone who’s written Unix shell commands, or Windows shell commands. knows that some characters have special superpowers, like “dollar-sign round brackets”, and “greater than” sign, which overwrites files, and the “pipe” character, which says to send the output into another command and run it.

So it was, if you like, poor attention to detail in an ancillary script that isn’t really part of the cryptographic library.

Basically, this is just a script that many people probably never considered, but it was delivered by OpenSSL; packaged in with it in many operating systems; popped into a system location where it became executable; and used by the system for what you might call “useful cryptographic housekeeping”.

So the version you want is 3.0.4, or 1.1.1p (P-for-Papa).

But having said that, while we’re recording this, there’s a big fuss going on about the need for OpenSSL 3.0.5, a completely different bug – a buffer overflow in some special accelerated RSA cryptographic calculations, which is probably going to need fixing.

So, by the time you hear this, if you’re using OpenSSL 3, there might be yet another update!

The good side, I suppose, Doug, is that when these things do get noticed, the OpenSSL team do seem to get onto the problem and push out patches pretty quickly.

DOUG. Great.

We’ll keep an eye on that, and keep an eye out for 3.0.5.

DUCK. Yes!

Just to be clear, when 3.0.5, there won’t be a matching 1.1.1q (Q-forQuebec), because this bug is a new code that was introduced in OpenSSL 3.

And if you’re wondering… just like the iPhone never had iPhone 2, there was no OpenSSL 2.

DOUG. OK, we’ve got some advice, starting with: Update OpenSSL as soon as you can, obviously.

DUCK. Yes.

Even though this is not in the cryptographic library but in a script, you might as well update, because if your operating system has the OpenSSL package, this buggy script will almost certainly be in it.

And it will probably be installed where somebody with your worst interests at heart could probably get at it, possibly even remotely, if they really wanted to.

DOUG. OK, with that: Consider retiring the c_rehash utility if you’re using it.

DUCK. Yes, that c_rehash is actually a legacy perl script that runs other programs insecurely.

You can now actually use a built-in part of the OpenSSL app itself: openssl rehash.

If you want to know more about that, you can just type openssl rehash -help.

DOUG. All right.

And then, we’ve said this time and time again: Sanitise your inputs and outputs.

DUCK. Absolutely.

Never assume that input that you get from someone else is safe to use just as you received it.

And when you’ve processed data that you received from elsewhere, or that you’ve read in from somewhere else, and you’re going to hand it on to someone else, do the nice thing and check that you’re not passing them dud information first.

Obviously, you would hope that they would check their inputs, but if you check your outputs as well, then it just makes assurance double sure!

DOUG. OK. And then finally: Be vigilant for multiple errors when reviewing code for specific types of bug.

DUCK. Yes, I thought that was worth reminding people about.

Because there was one bug, where Perl performed what’s called command substitution, which says, “Run this external command with these arguments, get the output, and use the output as part of the new command.”

It was in sending the arguments to that command that something went wrong, and that was patched: a special function was written that checked the inputs properly.

But it seems that nobody went through really carefully and said, “Did the person who wrote this utility originally use a similar programmatic trick elsewhere?”

In other words, maybe they shell out to a system function elsewhere in the same code… and if you looked more carefully, you would have found it.

There’s a place where they do a hash calculation using an external program, and there’s a place where they do file copying using an external function.

One had been checked and fixed, but the other had not been found.

DOUG. All right, good advice!

That article is called: OpenSSL issues a bugfix for the previous bugfix, on nakedsecurity.sophos.com.

And, as the sun slowly begins to set on our show for today, let’s hear from one of our readers on the OpenSSL article we just discussed.

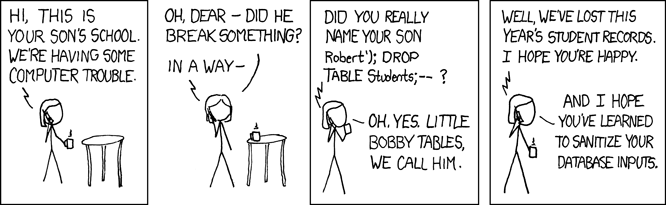

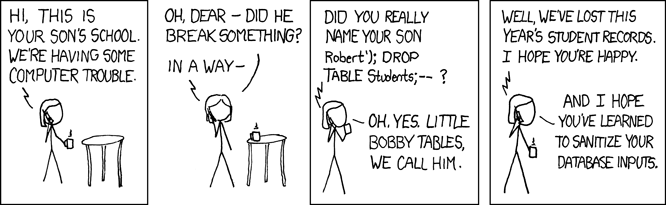

Reader Larry links to an XKCD Web comic called Exploits of a Mom… I implore you to go and find it.

I realise that me trying to verbally explain a web comic is not really great fodder for a podcast, so go to https://xkcd.com/327 and see it yourself.

DUCK. All you need to do, Doug, because many listeners will have thought, “I’m honestly hoping that someone would commented this”… I was!

It’s the one about Little Bobby Tables!

DOUG. All right…

DUCK. It’s become a kind of internet meme in its own right.

DOUG. The scene opens up.

A mom gets a phone call from her son’s school that says, “Hi, this is your son’s school. We’re having some computer trouble.”

And she says, “Oh, dear, did he break something?”

And they say, “In a way. Did you really name your son Robert'); DROP TABLE Students;--?”

“Oh, yes. Little Bobby Tables, we call him.”

And they say, “Well, we’ve lost this year’s student records. I hope you’re happy.”

And she says, “And I hope you’ve learned to sanitize your database inputs.”

Very good.

DUCK. A little bit of a naughty mum… remember, we’re saying sanitize your inputs *and your outputs*, so don’t go out of your way to trigger bugs just to be a smarty-pants.

But she’s right.

They shouldn’t just take any old data that they’re given, make up a command string with it, and assume that it’ll all be fine.

Because not everybody plays by the rules.

DOUG. That’s from 2007, and it still holds up!

If you have an interesting story, comment or question you’d like to submit, we’d love to read it on the podcast.

You can email tips@sophos.com; you can comment on any one of our articles; or you can hit us up on social: @nakedsecurity.

That’s our show for today.

Thanks very much for listening… for Paul Ducklin, I’m Doug Aamoth, reminding you until next time to…

BOTH. …stay secure!

[MUSICAL MODEM]